Early Native American Ceramics In Virginia

Back to Native American Ceramics Home

Native Americans have made ceramics continuously in Virginia for more than 3,200 years. Pottery manufacture in North America first arose more than 4,200 years ago in the coastal plain of Georgia and spread north from there. Pottery production was a cottage industry, conducted by families with the knowledge of manufacture handed down from mother to daughter. Archaeologists have defined more than 60 Native American wares applicable to Virginia, recording the variables in vessel size and shape, temper, surface treatment and decoration of pottery from 1200 BCE to the present. This wealth of pottery information provides archaeologists with ways to date sites, and to describe Native American social groups and interpret their interaction, movement, blending, and fluidity.

Origins of Ceramics

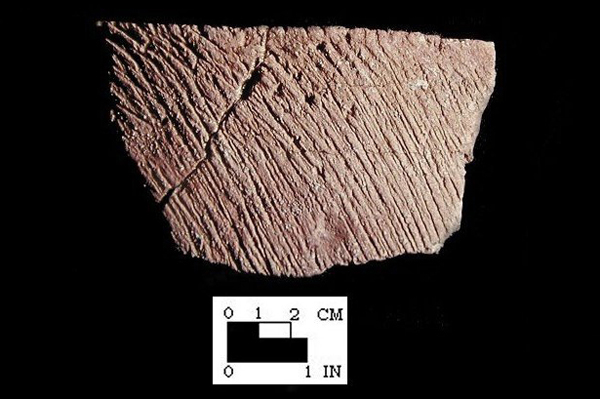

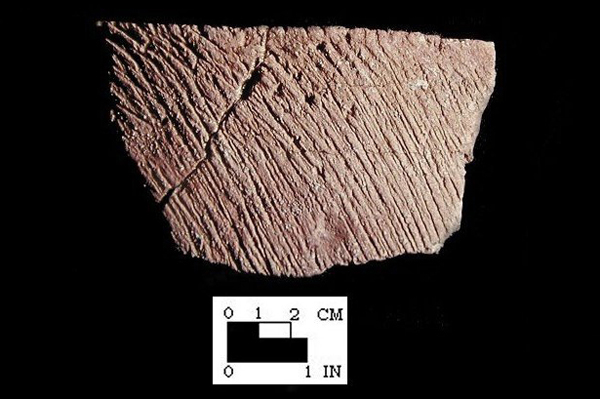

Since the early 20th century, archaeologists have searched for the earliest ceramics in Virginia, discussed their origin of manufacture, and debated their impact on developing Native American societies. The earliest dated pottery from Virginia is Bushnell Ware defined and dated at the White Oak Point shell midden along the Potomac River in Westmoreland County. Three radiometric samples yielded an average uncorrected date of 3060 BP.

Since the early 20th century, archaeologists have searched for the earliest ceramics in Virginia, discussed their origin of manufacture, and debated their impact on developing Native American societies. The earliest dated pottery from Virginia is Bushnell Ware defined and dated at the White Oak Point shell midden along the Potomac River in Westmoreland County. Three radiometric samples yielded an average uncorrected date of 3060 BP.

But, where did the idea originate for the earliest pottery in Virginia? There are two possible interpretations: 1) the technology evolved locally as an independent invention drawing inspiration from the manufacture of earlier containers such as soapstone bowls, and 2) pottery manufacture evolved elsewhere and was introduced into Virginia.

Soapstone Containers

Archaeologists have noted the close resemblance of early pottery and carved soapstone containers, which were manufactured in Virginia by 2500 BCE. Native Americans fashioned soapstone into thick heavy oval and round shaped containers, a few appearing like mortars, but also rather elegant, thin bowls. Black smudges on soapstone vessels indicate that they were used for cooking. Soapstone vessel manufacture was limited to a few places in Virginia where the stone occurs naturally. Archaeologists have identified quarries in Fairfax, Orange, Madison, Albemarle, Nelson, Amelia, and Brunswick counties. Manufacturing vessels, as well as establishing trade networks and transporting and repairing soapstone vessels, took a great deal of effort. Furthermore, there probably existed competition for vessels, and only a small social segment of the people were able to afford and obtain the containers.

The original demand for soapstone vessels may have created a need for inexpensive durable vessels that could be produced anywhere from local clays and used by everyone. Although the quarries contained an unending supply of soapstone, the production and exchange networks may not have been able to meet the demand. This may in part explain why ceramic production was accepted first in areas far removed from soapstone quarries.

When people in Virginia decided to make pottery, they quickly discontinued the use of soapstone containers. The earliest ceramic vessels are approximately the same size and shape as soapstone vessels and have similar lug handles. Early pottery vessels even contain soapstone, perhaps broken pieces of stone containers, as temper in their paste. Archaeologists interpret this as a symbolic transference of strength and durability from the stone containers to the ceramic vessels.

Oldest Pottery in North America

The oldest pottery tradition in North America consists of fiber-tempered wares traced to the coast of present-day Georgia and northeast Florida. This pottery dates to at least 2500 BCE. Shortly thereafter the innovation spread north and south along the Atlantic coast and into the interior. It took more than a thousand years for ceramic technology to spread five hundred miles north and to be accepted by people in Virginia.

But how and why was pottery created? There are four major hypotheses. With the first, the architecture hypothesis, the origin of pottery is found in the technology of wattle and daub or other architectural traditions, such as prepared clay hearths, where clay and fire come together. This hypothesis discusses solely the origin and not the use of pottery. With the culinary hypothesis, pottery is an adaptation that enables greater productivity by increasing efficiency in food preparation, detoxifying some previously inedible resources, providing softer foods, and increasing the storability of foods. In the resource-intensification hypothesis abundance or scarcity in specific environments and seasons is the trigger that led to ceramic production. The social/symbolic hypothesis emphasizes that early pottery is found in contexts that cannot be described as strictly utilitarian and in which some of the pottery is quite elaborate. Pottery thus emerges first as a ceremonial and prestige technology, the knowledge and use of which may have been controlled by leaders or ritual specialists.

The fact that many of the early pottery variants in Virginia were tempered with material other than soapstone and that they are found along the Coastal Plain of Virginia supports the interpretation that the innovation of pottery manufacture had a southern Atlantic origin. The concept of pottery making probably spread north along the Interior Coastal Plain trails which connected Georgia with Virginia. This early period is noted for the intensification of long distance travel and exchange. Thus, most archaeologists see the origins of pottery in Virginia not as an independent invention but as one arising out of the early fiber-tempered tradition in the Southeast. However, the Virginia experimentation of vessel shapes and temper draws inspiration from local soapstone containers.

Impact of Early Ceramics

For years a debate has existed among archaeologists in Virginia concerning whether or not the presence of ceramics in a society should reassign an otherwise Archaic stage of cultural development to a Woodland classification. The main question is whether the incorporation of pottery brought about any developmental change in the cultural systems of the societies. Many archaeologists believe that the addition of pottery had little overall affect on Native American societies. They view pottery as just a replacement for stone, woven, or wooden containers. Pottery, therefore, represented little more than transference of function to a different medium. Fundamental system changes resulting in greater residential stability, elaboration of the socio-political subsystem, and long distance exchange networks had developed before the introduction of pottery.

Other archaeologists think differently. They believe the fragility of ceramic vessels indicate that people now practiced a sedentary lifestyle. There are areas in Virginia where early ceramics existed and sedentism was of a greater intensity than that normally found in the Archaic stage of development. In addition, incorporating pottery into the existing system of producing containers from soapstone, wood, and fiber necessitated the addition of new procurement, manufacture, and use technologies. This effected to a lesser extent, other cultural subsystems concerned with symbolic values, trade, environmental exploitation, food preparation, and male and female roles. In Virginia, archaeologists use the earliest pottery as one of the fundamental criteria to mark the beginning of the Woodland stage of development.

Early Pottery Along the Coast

When Native Americans in Virginia decided to make pottery, they discontinued the use of soapstone containers. Though pottery vessels were fragile and easily broken, they could be replaced quickly. Superior cooking pots, they also provided drier storage than earlier fiber or skin vessels. In general, the earliest ceramics were made in the Coastal Plain of Virginia, in the Piedmont along the Potomac and James rivers, and along the lower Shenandoah River. Ceramics appeared later along the Roanoke River and along the river drainages that flow through the mountainous area of southwestern Virginia. Perhaps the variables of cultural isolation and interaction, distance from soapstone quarries, and degree of sedentism were involved with the differential acceptance of pottery.

Archaeologists have defined a number of ceramic wares that illustrate the early experimentation with hand-modeled construction, vessel shape, temper, and lug handles. Marcey Creek Ware was the first of the early pottery defined at the Marcey Creek Site on the Potomac River in Arlington County, Virginia. The ware was hand modeled on a flat base, which often bears impressions of the open-weave mat that the vessel was made on. The vessels are rectangular or oval shallow bowls with curved to straight sides and lug handles at the ends. The ware is found in small quantities throughout the Virginia Coastal Plain, along the James and Potomac rivers in the Piedmont, and in the Shenandoah Valley north of Port Republic.

Other similar early wares, their only obvious difference is temper, were eventually defined. They are all thought to date from 1200 to 800 BCE. Croaker Landing Ware, excavated at Croaker Landing along the York River in James City County, is an early Coastal Plain ware similar to Marcey Creek. However, it was tempered with clay or a combination of clay and soapstone. The ware is distributed in the southern Coastal Plain of Virginia. Waterlily Ware, defined from pottery found in Currituck County, North Carolina, is an early Coastal Plain ware similar to the other early wares, except that it is tempered with shell. It is found mainly in the Virginia Beach area. Ware Plain, exhibiting crushed-quartz temper, is found on the Delmarva Peninsula, the Eastern Shore of Virginia, in the Coastal Plain, and along the James River in the Piedmont. Bushnell Ware characterized by schist temper was first defined at the White Oak Point Site in Westmoreland County. It has been found in the northern Coastal Plain and also in the Piedmont along the James River.

Later Pottery in the Piedmont and Mountains

Similar early ceramics have not been identified in the upper James, Roanoke, New, or Powell/Clinch/Holston river drainages. Native Americans living in these drainage basins were more isolated from the concept of pottery production. However, by 500 BCE pottery was crafted across all of Virginia. By then a wide variety of vessel forms--shallow bowls, cooking jars, and extremely large storage vessels--were manufactured.

The earliest pottery along the Roanoke River in the Piedmont, Hyco Ware, is similar to Elk Island Ware, a sandy, friable pottery with plain and cord-marked surfaces, found along the James River. Both wares exhibit coil construction with rounded or conoidal bases and date to 800 BCE. In the mountainous region of southwestern Virginia the earliest identified ceramic is Swannanoa Ware, a crushed-quartz to sand-tempered pottery dating to 500 BCE that was first identified in western North Carolina.

Recent Pottery

For the last 325 years, women of the Pamunkey Nation made pottery, handcrafted from the clay dug from their reservation along the Pamunkey River. By the mid 18th century the Pamunkey made plates, cups, pipkins, chamber pots, and jars both for themselves and for sale to the colonists. They tempered the clay by mixing it with pulverized freshwater mussels. They then shaped the mixture by hand into a vessel, smoothed its surface, and burnished it with a rubbing stone. It was called Colono Indian Ware, defined in 1962. It was first recovered from colonial contexts, beginning in the last quarter of the 17th century, in the vicinity of Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown. Many examples of the ware have been found on the Pamunkey Reservation. It continued to be made into the first quarter of the 19th century.

Two other historic Native American wares were quickly identified in the Coastal Plain of Virginia. A similar historic pottery dating from CE 1675 to 1750, Courtland Ware, was defined from ceramics found in 1965 along the Nottoway River in Southampton County, Virginia. Presumably, this pottery was made by the Nottoway Indians. In 1965 a third historic pottery, called Camden Ware, was identified in Caroline County, along the Rappahannock River. It dates to the last quarter of the 17th century. This pottery probably was made by the Rappahannock Indians.

By the mid-19th century, railroads began to bring cheap, mass-produced kitchen wares into eastern Virginia, and the demand for the Pamunkey handmade pottery soon decreased. The craft was nearly extinct when, in 1932, a Virginia state official on a visit to the Pamunkey Reservation suggested that they try to sell pottery to tourists to supplement their meager income. The school’s first instructor respected his students’ traditions but also introduced them to the use of the potter’s wheel, molds, paints, and the baking kiln. In recent years, however, some potters have revived the older methods. Today tribal artisans follow both the ancient and modern traditions.

See Also:

Since the early 20th century, archaeologists have searched for the earliest ceramics in Virginia, discussed their origin of manufacture, and debated their impact on developing Native American societies. The earliest dated pottery from Virginia is Bushnell Ware defined and dated at the White Oak Point shell midden along the Potomac River in Westmoreland County. Three radiometric samples yielded an average uncorrected date of 3060 BP.

Since the early 20th century, archaeologists have searched for the earliest ceramics in Virginia, discussed their origin of manufacture, and debated their impact on developing Native American societies. The earliest dated pottery from Virginia is Bushnell Ware defined and dated at the White Oak Point shell midden along the Potomac River in Westmoreland County. Three radiometric samples yielded an average uncorrected date of 3060 BP.